Collaboration is key in esophageal cancer screening

More than a decade of research at ������ý, led by Fons van der Sommen, has culminated in a scientific publication in The Lancet Digital Health this December. The study focuses on the use of artificial intelligence (AI) to detect incipient esophageal cancer in people with Barrett's esophagus.

It is 2011. Gastroenterologist Erik Schoon of Catharina Hospital Eindhoven approaches ������ý Professor Peter de With to improve the effectiveness of preventive cancer screening. At the same time, Electrical Engineering student Fons van der Sommen decided that he wanted to apply his knowledge of computer vision to oncology. This confluence of circumstances forms the basis for an AI system that subsequently helps doctors to detect esophageal cancer at an early stage.

“If my iPhone can recognize faces in photos, why can’t we automatically recognize cancer in medical images?” This was the question with which approached the university, says Fons van der Sommen, now an associate professor at ������ý.

“At the time, I had halted my internship at Philips on the automatic recognition of people in video images because my father had become ill and died of a brain tumor. That experience motivated me to start applying my knowledge to the medical field. Peter de With linked me to Erik’s question and that’s how the ball got rolling.”

Successful completion

Ten years later, what once started out small with a single master’s project has blossomed into an extremely successful line of research, several cum laude doctorates, and a technique that has reached the clinic.

In a recent article in , the 31 research participants proved the added value of their AI system in recognizing the early signs of esophageal cancer in a specific group of patients based on a large-scale study.

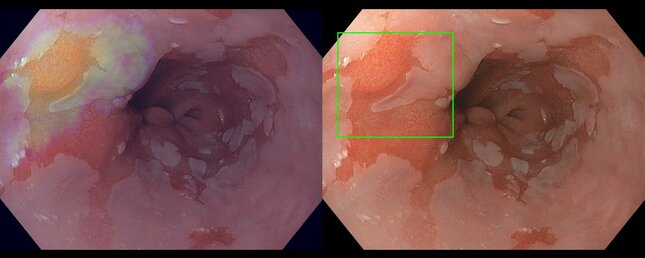

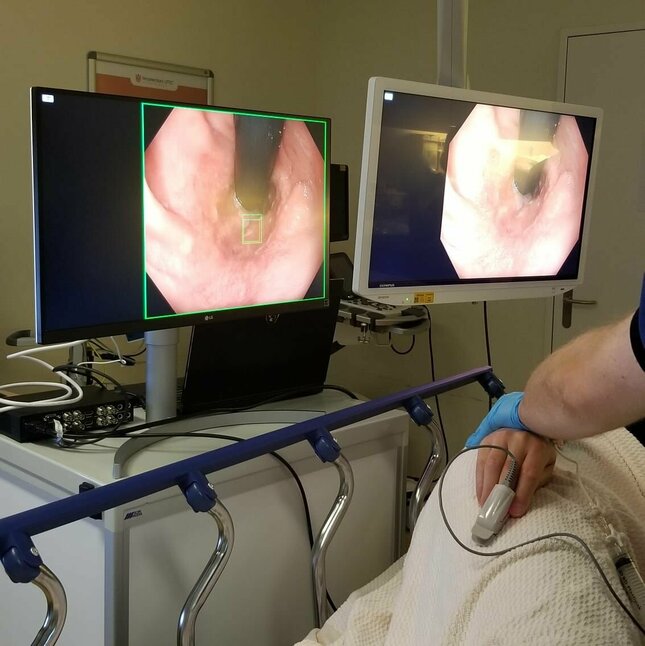

The AI system watches in real-time during an endoscopy – a procedure in which the doctor sends a light and a mini-camera down the esophagus. On the video footage, the system indicates in red where it sees suspicious tissue that needs further investigation through a biopsy.

In the meantime, the doctor reviews the images personally. One of the partners in the recently published research is Medical Systems, which will now implement the AI software in their endoscopy equipment so that doctors can start using it in hospitals.

Ideal test case

“The system that we present in the Lancet article is specifically trained to tell the difference between ‘normal’ Barrett’s tissue and cancer cells,” says Van der Sommen. Although this condition involves a relatively small number of patients, he argues that it is an ideal case to demonstrate the added value of AI for medical care.

It involves one of the most complex image analyses in the medical field: abnormalities in tissue, that already deviates from the norm.

Fons van der Sommen

“This is one of the most complex image analyses in the medical field. You’re looking for minimal abnormalities in tissue that is not normal in and of itself. ‘If we can do this, we can do anything,’ as Erik immediately said to me.”

Road to success

Looking back, Van der Sommen identifies a number of factors that were critical to the success of this study. “We started well by first talking extensively with doctors. What is and isn’t relevant to the clinical setting? What are they looking at in endoscopy images? What are the crucial differences between ‘normal’ Barrett’s tissue and cancerous tissue?”

“Based on those conversations and a hundred or so images of Barrett’s esophaguses with and without cancer, I created an initial algorithm that could automatically identify suspicious abnormalities.” That master’s research immediately resulted in three publications.

Meanwhile, funding had been awarded from the ‘’ program of NWO TTW (then STW) and KWF for a PhD program for Van der Sommen involving endoscopy manufacturer Fuji.

That project produced a system that, when tested at Amsterdam UMC and the Eindhoven-based Catharina Hospital, proved to score better than international endoscopists who assessed the image by eye.

Broadening the consortium

In addition, the Eindhoven research attracted the attention of of the Amsterdam UMC, the Dutch authority on Barrett’s esophagus.

“He had developed a new visualization technique to detect early esophageal cancer, but the results were difficult for humans to interpret. He was curious to see if we could automatically extract the clinically relevant information with our learning algorithms,” Van der Sommen says.

During his PhD period, Van der Sommen had developed algorithms that could recognize the early stages of cancer in images taken with this volumetric laser endomicroscopy technique. Due to the complexity of this measurement technique, however, it did not make it to the clinic.

“But our results convinced Bergman of the power of AI. He initiated a new, larger-scale project called ARGOS, led by the Barrett Expertise Center in Amsterdam,” continues Van der Sommen in his chronological narrative.

As that expertise center had close ties to endoscopy supplier Olympus, a collaboration with them seemed obvious. “In 2018, a delegation from that company came to the Netherlands from Tokyo. We presented them with our plans to improve the technical design of the system while also creating a large-scale database of gastric, liver and intestinal endoscopic images with which to train our systems.”

New technical challenges

In that conversation, some practical preconditions were immediately raised by Olympus and presented new technical challenges, explains the electrical engineer. “The algorithm we’d developed at the time for automatic image analysis required too much computing power and memory.”

“The processors that are standard in such an endoscope cannot handle this at all. In addition, the calculations still took too long; you want to be able to point out deviations in real-time. Together with clinical PhD student Jeroen de Groof of the Amsterdam UMC, PhD students Joost van der Putten, Tim Boers, and Koen Kusters, among others, therefore spent a lot of time and energy adapting our architecture to make image processing feasible in clinical practice.”

A large-scale study included training the new AI algorithm to quickly and efficiently recognize abnormalities in endoscopic photographs and videos of Barrett’s esophagus. “The beauty of the overview research now published in the Lancet is that we tested the system on data that we carefully left out of the development (the training and validation). And that we also only used this external test set once,” says Van der Sommen.

As a result, the system did not copy the correct answers from a previous test like a cheating student but instead assessed each image for the first time based on the knowledge that the system had gained from other images. In this way, Van der Sommen is certain that the system will also perform as well with new, real images in practice in each hospital.

We want to close the gap between teaching hospitals and area hospitals.

Fons van der Sommen

Exploring boundaries

In a follow-up study funded by an NWO Veni grant, Van der Sommen is now exploring the limits of the technology. “We want to close the gap between specialist hospitals and regional hospitals. Most hospitals do not have the latest equipment to work with nor do they have the time to make endoscopy images as nice as possible.”

“So, we’re now looking at what’s possible with images that have a poorer resolution, are overexposed or are blurry. And maybe there are differences in patient populations that we need to take into account in our algorithms.”

He is also working with Erik Schoon and Maastricht UMC, among others, on a follow-up study to automatically recognize malignant structures in the colon. “And we are looking at what we can do with our technology regarding the early detection of lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, and prostate cancer,” the Eindhoven scientist says with satisfaction.

Collaboration between physician and AI is key.

Fons van der Sommen

In all cases, collaboration between the doctor and the AI is central, he emphasizes. “When we started this in 2011, there was still great resistance to the idea of allowing artificial intelligence into the clinic. The idea was that you cannot replace doctors with a robot. I completely agree with that.”

“An artificially intelligent system that can do exactly the same thing as a human being has zero added value. It is by extracting different information from an image that we can broaden the doctor’s view and thus improve care. And then it’s also no big deal if the AI overlooks something that is plain as day to a human doctor.”

The article ‘’, authored by of Amsterdam UMC and Fons van der Sommen, among others, appeared online in The Lancet Digital Health in late November and in the paper edition of the scientific journal in December.

Related News

Health Week 2025: cancer research in the spotlight

More on AI and Data Science

Latest news